Introduction to the Domain Name System (DNS)

Learn how the global DNS system makes it possible for us to assign memorable names to the worldwide network of machines we connect to every day.

Surfing the web is fun and easy, but think what it would be like if you had to type in the IP address of every website you wanted to view. For example, locating a website would look like this when you type it in your browser: 45.20.209.41, which would be nearly impossible for most of us to remember. Of course, using bookmarks would help, but suppose your friend tells you about a cool new website and tells you to go to 45.20.209.41. How would you remember that? Telling someone to go to “Both.com” is far easier to remember. And, yes, that is our IP address.

The Domain Name System provides the database to be used in the translation from human-readable hostnames, such as www.both.org, to IP addresses, like 93.184.216.34, so that your internet-connected computers and other devices can access them. The primary function of the BIND (Berkeley Internet Name Domain) software is that of a domain name resolver that uses that database. There are other name resolver software, but BIND is currently the most widely used DNS software on the internet. I will use the terms name server, DNS, and resolver pretty much interchangeably throughout this article.

Without these name resolver services, surfing the web as freely and easily as we do would be nearly impossible. As humans, we tend to do better with names like Opensource.com, while computers do much better with numbers like 93.184.216.34. Therefore, we need a translation service to convert the names that are easy for us to the numbers that are easy for our computers.

In small networks, the /etc/hosts file on each host can be used as a name resolver. Maintaining copies of this file on several hosts can become very time-consuming and errors can cause much confusion and wasted time before they are found. I did this for several years on my own network and it eventually became too much trouble to maintain even with only the usual eight to 12 computers I usually have operational. Ultimately, I converted to running my own name server to resolve both internal and external hostnames. Figure 1 is an example of a simple /etc/hosts file.

127.0.0.1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost4 localhost4.localdomain4::1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost6 localhost6.localdomain6

# Lab hosts

192.168.25.1 server

192.168.25.21 host1

192.168.25.22 host2

192.168.25.23 host3

192.168.25.24 host4Figure 1: A simple /etc/hosts file.

Most networks of any size require centralized management of this service with name services software such as BIND. Hosts use the Domain Name System (DNS) to locate IP addresses from the names given in software such as web browsers, email clients, SSH, FTP, and many other internet services.

How a name search works

Let’s take look at a simplified example of what happens when a name request for a web page is made by a client service on your computer. For this example, I will use www.Both.org as the website I want to view in my browser. I also assume that there is a local name server on the network, as is the case with my own network.

- First, I type in the URL or select a bookmark containing that URL. In this case, the URL is www.Both.org.

- The browser client, whether it is Opera, Firefox, Chrome, Lynx, Links, or any other browser, sends the request to the operating system.

- The operating system first checks the /etc/hosts file to see if the URL or hostname is there. If so the IP address of that entry is returned to the browser. If not, I proceed to the next step. In this case, I assume that it is not.

- The URL is then sent to the first name server specified in /etc/resolv.conf. In this case, the IP address of the first name server is my own internal name server. For this example, my name server does not have the IP address for www.Both.org cached and must look further afield. Let’s go on to the next step.

- The local name server sends the request to a remote name server. This can be one of two destination types, one type of which is a forwarder. A forwarder is simply another name server, such as the ones at your ISP, or a public name server, such as Google at 8.8.8.8 or 8.8.4.4. The other destination type is that of the top-level root name servers. The root servers don’t usually respond with the desired target IP address or www.Both.org, they respond with the authoritative name server for that domain. The authoritative name servers are the only ones that have the authority to maintain and modify name data for a domain. The local name server is configured to use the root name servers so the root name server for the .com top-level domain returns the IP address of the authoritative name server for www.Both.org. That IP address could be for any one of the three (at the time of this writing) name servers, ns1.redhat.com, ns2.redhat.com, or ns3.redhat.com.

- The local name server then sends the query to the authoritative name server, which returns the IP address for www.Both.org.

- The browser uses the IP address for www.Both.org to send a request for a web page, which is downloaded to my browser.

One of the important side effects of this name search is that the results are cached for a period of time by my local name server. That means that the next time I, or anyone on my network, wants to access Opensource.com, the IP address is probably already stored locally, which prevents doing a remote lookup.

The DNS database

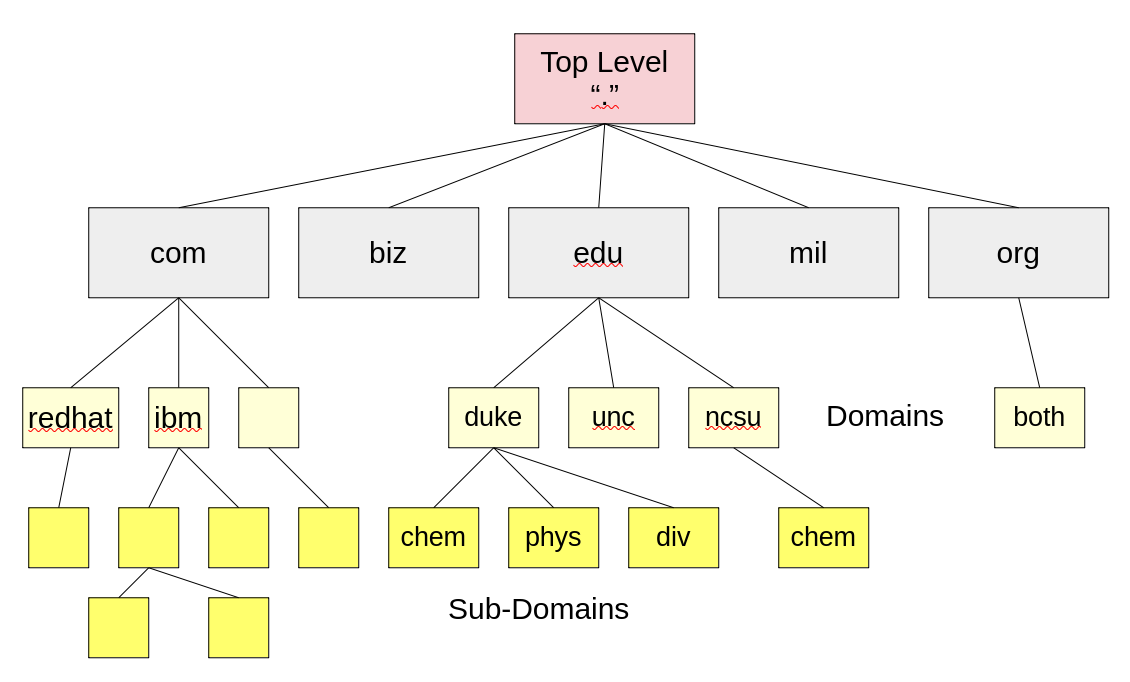

The DNS system is dependent upon its database to perform lookups on hostnames to locate the correct IP address. The DNS database is a general-purpose, distributed, hierarchical, replicated database. It also defines the style of hostname used on the internet, properly called a FQDN (Fully Qualified Domain Name). By “distributed, we mean that the data is stored on many servers around the world, each server having only a portion of the total data.

FQDNs consist of complete hostnames such as hornet.example.com and test1.example.com. FQDNs break down into three parts.

- The TLDN (Top-Level Domain Names), such as .com, .net, .biz, .org, .info, .edu, and so on, provide the last segment of a FQDN. All TLDNs are managed on the root name servers. Aside from country top-level domains such as .us, .uk, and so on, there were originally only a few main top-level domains. As of February 2017, there are 1528 top-level domains.

- The second level domain name is always immediately to the left of the top-level domain when specifying a hostname or URL, so names like Redhat.com, Opensource.com, Getfedora.org, and example.com provide the organizational address portion of the FQDN.

- The third level of the FQDN is the hostname portion of the name, so the FQDN of a specific host in a network would be something like host1.example.com.

Figure 2 shows a simplified diagram of the DNS database hierarchy. The “top” level, which is represented by a single dot (.) has no real physical existence. It is a device for use in DNS zone file configuration to enable an explicit end stop for domain names. A bit more on this later.

The true top level consists of the root name servers. These are a limited number of servers that maintain the top-level DNS databases. The root level may contain the IP addresses for some domains, and the root servers will directly provide those IP addresses where they are available. In other cases, the root servers provide the IP addresses of the authoritative server for the desired domain.

For example, assume I want to browse www.example.org. My browser makes the request of the local name server, which does not contain that IP address. My local name server is configured to use the root servers when an address is not found in the local cache, so it sends the request for www.example.org to one of the root servers. Of course, the local name server must know how to locate the root name servers so it uses the /var/named/named.ca file, which contains the names and IP addresses of the root name servers. The named.ca file is also known as the hints file.

In this example, the IP address for www.example.org is not stored by the root servers. The root server uses its database to locate the name and IP address of the authoritative name server for www.example.org.

The local name server queries the authoritative name server, which returns the IP address of www.example.org. The local name server then responds to the browser’s request and provides it with the IP address. The authoritative name server for Opensource.com contains the zone files for that domain.

Figure 3 shows the results of a dig command displaying not only the IP address of the desired host, but it also shows the authoritative servers, their IP addresses, and the server that actually fulfilled the request. Here is the use of the dig command that obtains the DNS information for www.example.org. The dig command is a powerful tool that can tell us a lot of information about the DNS configuration for a host. The dig command returns the actual records from the DNS database and displays the results in four main sections. Refer to Figure 3 as you read the descriptions of these sections.

# dig www.redhat.com

; <<>> DiG 9.18.24 <<>> www.redhat.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 41966

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 4, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

; COOKIE: d4e96abc809535f501000000660efab7c34f3153cca4720c (good)

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;www.redhat.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

www.redhat.com. 3600 IN CNAME ds-www.redhat.com.edgekey.net.

ds-www.redhat.com.edgekey.net. 4016 IN CNAME ds-www.redhat.com.edgekey.net.globalredir.akadns.net.

ds-www.redhat.com.edgekey.net.globalredir.akadns.net. 3600 IN CNAME e3396.dscx.akamaiedge.net.

e3396.dscx.akamaiedge.net. 20 IN A 23.202.2.35

;; Query time: 396 msec

;; SERVER: 192.168.0.52#53(192.168.0.52) (UDP)

;; WHEN: Thu Apr 04 15:08:39 EDT 2024

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 235Figure 3: The results of a dig command for www.redhat.com

The first section is the query section. For this example, it states that I am looking for the A record of “www.redhat.com”.

The answer section shows four entries, three CNAME records and an A record. A records are the primary name resolver records and there must be an A record, which contains the IP address for each host. CNAME stands for Canonical Name and this record type is an alias for the A record and points to it. It is not typical practice to use “www” as the hostname for a web server. It is common to see a CNAME record that points to the A record of the FQDN; however, that is not quite the case here. Notice that the A record does not have a hostname associated with it. It is possible to have a record that applies to the domain as a whole as is the case here.

If an authority section were present, it would list the authoritative name servers for the FQDN. The record type is NS for those entries.

The last section shows some additional interesting information, including the IP address of the server that returned the information shown in the results. In this case, it was my own internal name server.

DNS Client configuration

Most computers need little configuration to enable them to access name services. It usually consists of adding the IP addresses of one to three name servers to the /etc/resolv.conf file. This is typically performed at boot time on most home and laptop computers because they are configured using the DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol), which provides them with their IP address, gateway address, and the IP addresses of the name servers.

For hosts that are configured statically, the resolv.conf file is usually generated during installation from information entered by the sysadmin doing the install. In current Red Hat-based distributions and others that use NetworkManager to manage network configuration and to perform connection management, the static information, such as name servers, gateway, and IP address, are all stored in the interface configuration files located in /etc/sysconfig/network-scripts.

Overriding the defaults provided to a host by adding that information to the interface configuration file is possible. For example, I sometimes add my preferred name servers to the interface configuration files on my laptop and netbook. Many of the name servers provided by remote connections in public places, such as hotels, coffee shops, and even friends’ personal Wi-Fi connections, can be unreliable and in some cases can use forwarders that intentionally censor results or redirect queries to pages of advertisements, so I always insert the Google public name servers in my network configuration.

Also, be aware that NetworkManager creates a network connection file for each Wi-Fi network it connects with. The connection files are named for the SSID (Service Set IDentifier) of the network. Be sure to add the desired name server entries to the correct file.

Here’s an example of a network connection file that’s been created on my laptop by NetworkManager in the last few months, MarriottBonvoy_Guest.nmconnection. this file contains the following configuration data. That makes connection easier next time I stay there.

[connection]

id=MarriottBonvoy_Guest

uuid=97ca6908-df7f-4148-a098-bfb2471dadf5

type=wifi

interface-name=wlp0s20f3

[wifi]

mode=infrastructure

ssid=MarriottBonvoy_Guest

[ipv4]

method=auto

[ipv6]

addr-gen-mode=default

method=auto

[proxy]

Figure 4: Contents of a typical NetworkManager connection file.

DNS record types

There are a number of different DNS record types, and I want to introduce some of the more common ones here. A future article will describe how to create your own name server using BIND and will use many of these record types to build your name server. These record types are used in the zone files that comprise the DNS database.

One common field in all of these records is “IN,” which specifies that these are INternet records.

View a complete list of DNS record types on Wikipedia.

SOA

SOA is the Start of Authority record. It is the first record in any forward or reverse zone file, and it identifies this as the authoritative source for the domain it describes. It also specifies certain functional parameters. A typical SOA record looks like the sample below.

@ IN SOA epc.example.com root.epc.example.com. (

2017031301 ; serial

1D ; refresh

1H ; retry

1W ; expire

3H ) ; minimum

The first line of the SOA record contains the name of the server for the zone and the zone administrator, in this case root.

The second line is a serial number. In this example, I use the date in YYYYMMDDXX format where XX is a counter. Thus, the serial number in the SOA record above represents the first version of this file on March 13, 2017. This format ensures that all changes to the serial number are incremented in a numerically sequential manner. Doing this is important because secondary name servers only replicate from the primary server when the serial number of the zone file on the primary is greater than the serial number on the secondary. Be sure to increment the serial number when you make changes or the secondary server will not sync up with the modified data.

The rest of the SOA record consists of various times that secondary servers should perform a refresh from the primary and wait for retries if the first refresh fails. It also defines the amount of time before the zone’s authoritative status expires.

Times all used to be specified in seconds, but recent versions of BIND allow other options defined with W=week, D=day, H=hour, and M=minute. Seconds are assumed if no other specifier is used.

$ORIGIN

The $ORIGIN record is like a variable assignment. The value of this variable is appended by the BIND program to any name in an A or PTR record that does not end in a period (.) in order to create the FQDN (Fully Qualified Domain Name) for that host. This makes for less typing because the zone administrator only has to type the host name portion and not the FQDN for each record.

$ORIGIN example.com.The @ symbol is used as a shortcut for this variable and any occurrence of @ in the file is replaced by the value of $ORIGIN.

NS

The NS record specifies the authoritative name server for the zone. Note that both names in this record end with periods so that “.example.com” does not get appended to them. This record will usually point to the local host by its FQDN.

example.com. IN NS epc.example.com.Note that the host, epc.example.com, must also have an A record in the zone. The A record can point to the external IP address of the host or to the localhost address, 127.0.0.1.

A

The A record is the Address record type that specifies the relationship between the host name and the IP address assigned to that host. In the example below, the host test1 has IP address 192.168.25.21. Note that the value of $ORIGIN is appended to the name test1 because test1 is not an FQDN and does not have a terminating period in this record.

test1 IN A 192.168.25.21The A record is the most common type of DNS database record.

CNAME

The CNAME record is an alias for the name in the A record for a host. For example, the hostname server.example.com might serve as both the web server and the mail server. There would be one A record for the server, and possibly two CNAME records as shown below.

server IN A 192.168.25.1

www IN CNAME server

mail IN CNAME serverLookups with the dig command on www.example.com and mail.example.com will return the CNAME record for mail or www and the A record for server.example.com.

PTR

The PTR records are to provide for reverse lookups. This is when you already know the IP address and need to know the fully qualified host name. For example, many mail servers do a reverse lookup on the alleged IP address of a sending mail server to verify that the name and IP address given in the email headers match. PTR records are used in reverse zone files. Reverse lookups can also be used when attempting to determine the source of suspect network packets.

Be aware that not all hosts have PTR records, and many ISPs create and manage the PTR records, so reverse lookups may not provide the needed information.

MX

The MX record defines the Mail eXchanger, (i.e., the mail server for the domain example.com). Notice that it points to the CNAME record for the server in the example above. Note that both example.com names in the MX record terminate with a dot so that example.com is not appended to the names.

; Mail server MX record

example.com. IN MX 10 mail.example.com.Domains may have multiple mail servers defined. The number “10” in the above MX record is a priority value. Other servers may have the same priority or different ones. The lower numbers define higher priorities. Therefore, if all mail servers have the same priority they would be used in round-robin fashion. If they have different priorities, the mail delivery would first be attempted to the mail server with the highest priority—the lowest number—and if that mail server did not respond, delivery would be attempted to the mail server with the next lower priority.

Other records

There are other types of records that you may encounter in the DNS database. One type, the TXT records, are used to record comments about the zone or hosts in the DNS database. TXT records can also be used for DNS Security. The rest of the DNS record types are outside the scope of this article.

Final thoughts

Name services are a very important part of making the internet easily accessible. It binds the myriad disparate hosts connected to the internet into a cohesive unit that makes it possible to communicate with the far reaches of the planet with ease. It has a complex distributed database structure that is perhaps even unknowable in its totality, yet that can be rapidly searched by any connected device to locate the IP address of any other device that has an entry in that database.

If you are a system administrator on a network of almost any size, you may find it helpful to know how to build your own name server. I will describe how you can do that in a future article.